Friday Reflection: More Than Just the Flower

Lindsay Schackenbach Regele on Joel Poinsett, Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Self-Interest

Throughlines

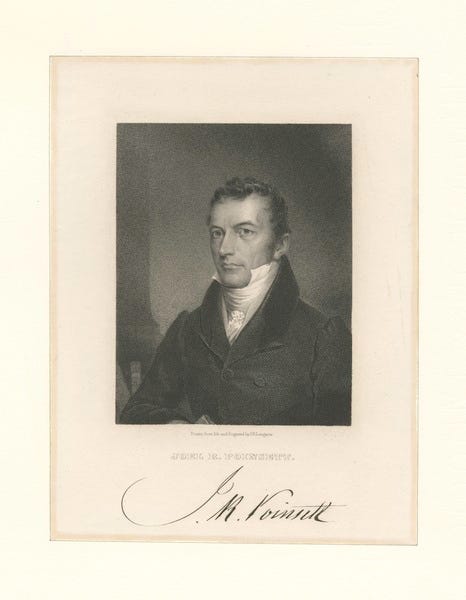

Joel Roberts Poinsett enters the conversation already wrapped in paradox. As you note in the introduction, the plant that bears his name — the poinsettia, the “cuetlaxochitl,” the noche buena — is a vivid and seasonal thing. But Poinsett himself is far more variegated, a man who seemed determined to occupy as many identities as possible without ever settling fully into any of them. Lindsay Schakenbach Regele, returning to the podcast, guides us through this improbable life in all its contradiction and mobility.

Poinsett begins as the child of Loyalists at the sharpest possible angle to American patriot mythology: born in Charleston in 1779, spirited off to England when the British evacuated the city in 1782, and raised there until the age of nine. When the family returns to South Carolina in 1787 or ’88, the boy probably arrived with an English accent — an outsider in a place that had been his birthplace. As Regele describes it, this becomes Poinsett’s lifelong pattern: always able to fit into a society, but never fully of it.

His education only reinforces the theme. He spends formative years in Connecticut at an academy run by the formidable Timothy Dwight, grandson of Jonathan Edwards, and heir to New England’s Calvinist intellectual tradition. Then comes more schooling in Britain, followed by a Grand Tour stretching through Europe into Russia. These are the years of Poinsett the cosmopolitan: fluent in French, nearly fluent in Spanish, and ambitious for a military career he never quite attains. He travels down the Volga with Lord Royston, past the Caspian into Persia, carrying himself — and sometimes behaving — like a Romantic aristocrat playing at adventure. As Regele notes, these travels are frustratingly undocumented; Poinsett simply did not write much. But what glimpses survive reveal a curious, acquisitive mind, alert to botany, geology, and social customs, sometimes charmingly observant, sometimes appallingly self-assured.

His first significant public role came when President Madison’s State Department sent him as a kind of confidential agent to the Río de la Plata and then Chile during the South American independence struggles. His instructions were vague; communications were slow; oversight was nonexistent; the result was predictable. Poinsett throws himself into the political turmoil, befriending revolutionary José Miguel Carrera, helping draft a constitution, and even taking up arms. He was part spy, part political advisor, part enthusiastic meddler — an American representative in an era before the United States quite knew what representing itself in South America meant.

Returning home in the 1820s, Poinsett became two things he had never been: not just a South Carolinian, but a politician. With the help of longstanding Charleston friendships, Poinsett is elected to the legislature, became a member of the Board of Public Works, and throws himself into the mania for canals, bridges, and internal improvements within the state. He was soon elected to Congress, and from there dispatched to Mexico as America’s first ambassador.

Mexico proves another stage for his talent for friction. Poinsett inserted himself into internal politics, established a rival Masonic lodge to counter the British influence promulgated through the Scottish Rite Masons, promoted American mining interests (including investments of doubtful solvency), and in five years managed to irritate almost every faction within the new republic. He also collected and sent to botanists in Philadelphia the plant which is eventually named after him.

Yet this stormy term in Mexico delivers him his most consequential role. During the nullification crisis between South Carolina and the federal government, Poinsett became Jackson’s unofficial man on the ground in Charleston — reporting in secret letters, distributing arms to unionists, and helping maintain federal authority in a state threatening disunion. While unpopular with much of the state’s elite, he now had a political base with Unionists in South Carolina. And his loyalty to the union earned him appointment as Secretary of War under Jackson’s successor Martin Van Buren.

In that office, Poinsett presides over the most sordid chapter of his career: the execution of Indian Removal and initiation of the Second Seminole War against those who refused to be deported into the west. Not only did he direct the forced removal of the Cherokee and others in 1837–38, he authorized the purchase and use of Cuban bloodhounds to track down Seminoles in the Florida wilderness — a decision that made him at the time a villain , at least in the Whig press. It is an indelible stain, and Regele treats it with clear-eyed candor.

Late in life, Poinsett married, became a substantial plantation owner and enslaver through marriage, and flirted with the long-held American obsession for acquiring Cuba. Yet he remainsed, improbably, an anti-secession unionist until his death in 1851. Perhaps a final paradox in a life full of them was that in this one case he did not change a mind or pattern of life that he had so often changed before.

Al and Lindsay finish the discussion by touching on the challenges confronting a biographer. He asks her if she came to dislike Poinsett in the course of writing the book. She admits that, given the feedback she has had from some readers, perhaps she was too hard on Poinsett in the book. While he was certainly morally compromised in several ways, he was also interesting, and she wonders if she failed to emphasize that.

Questions for Reflection & Discussion

How does Poinsett’s early life — especially his Loyalist family’s sojourn in England — shape his cosmopolitanism and his lifelong sense of being both inside and outside American identity?

To what degree is Poinsett representative of early American foreign policy improvisation? What does his South American mission suggest about the improvisational character of U.S. diplomacy before professionalization?

Why was Poinsett so drawn toward military glory, and how does that ambition recur throughout his life in unexpected places?

What does his involvement in Masonic politics in Mexico reveal about informal diplomacy, covert influence, and 19th-century political networks?

How should we morally evaluate someone like Poinsett, who could be simultaneously a scientific-minded cosmopolitan and a central executor of Indian removal?

In what ways do Poinsett’s actions in Mexico blur the line between personal enterprise and national interest? Was this typical or exceptional for American officials of his era?

How does the nullification crisis illuminate Poinsett’s political worldview, particularly his devotion to union over local loyalty?

What does Poinsett’s career suggest about the relationship between nationalism and expansionism in the antebellum United States?

How should we understand the way contemporaries viewed him — admired in some quarters, despised in others — and what does that tell us about the political fractures of the period?

After hearing this conversation, what paradox or contradiction in Poinsett’s life stays with you the most? Why?

For Further Investigation

Books

Lindsay Schakenbach Regele, Flowers, Guns, and Money: Joel Roberts Poinsett and the Paradoxes of American Patriotism (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

—, Manufacturing Advantage: War, the State, and the Origins of American Industry, 1776–1848 (Hopkins, 2019)

Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford University Press, 2009)

Michael Blaakman, Speculation Nation: Land Mania in the Revolutionary American Republic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024)

For the roots of land speculation.

Emilie Connolly’s Vested Interests: Trusteeship and Native Dispossession in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2025)

Michel Gobat, Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (Harvard University Press, 2018)

Walker operated in the 1850s, but this is helpful for understanding what some of Poinsett’s adventures eventually led to.

James E. Lewis, Jr., The American Union and the Problem of Neighborhood

The United States and the Collapse of the Spanish Empire, 1783-1829 (University of North Carolina Press, 1998)

Situates Poinsett in the broader story.

Claudio Saunt, Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory (W.W. Norton and Company, 2020)

Essential for contextualizing Poinsett’s role in the execution of Indian Removal.

Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America (Hill & Wang, 2012)

Related Episodes

Unsavory American founders and their scams, grifts, and cons

On the importance of foreign policy for forming the national identity of the early American Republic

About Southerners from the deep South who fought for the Union, and why they did it

How foreign policy was intimately connected to the politics of the Early American Republic

Primary Sources & Archives

The Papers of Joel Roberts Poinsett (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Pre-1861 U.S. foreign relations materials— documents regardung U.S. diplomatic instructions and correspondence.

The American State Papers: Military Affairs — includes correspondence relevant to Poinsett’s tenure as Secretary of War.